Issue #10 - I Wanna Be Bob Dylan

Things Have Changed

Bob Dylan was supposed to play in Amarillo this week. I was going to take my mom for her birthday. He was almost 18 when she was born, which if memory serves me, means he was about to move to Minneapolis and steal a bunch of folk records from one of his friends. Borrow rather, and never return.

When Alicia Keys was born in Hell’s Kitchen (she and I were born on the same day), Bob Dylan was living down the line, so he says in “Thunder on the Mountain.” 1981 was known as New York City’s “Most Violent Year.” It led to a lot of government and policing change, which was probably necessary, but also put them on a trajectory that winds up in Eric Garner. But I guess if someone as beautiful and talented as Alicia Keys could come out of the most dangerous section of New York City’s worst year, then maybe things will never get too bad.

In 1986, Dylan and Sam Shephard wrote an 11-minute sprawl of a song called “Brownsville Girl.” He sings about Gregory Peck westerns and a girl with curls and teeth like pearls, but smack in the middle, the narrator drives through Amarillo, looking for a friend named Henry Porter (later we find out that Henry Porter isn’t really named Henry Porter–such a Dylan sleight-of-hand). Instead, he finds a woman named Ruby living in a junkyard. She says corruption runs rampant in town; she says times are tough, but doesn’t ask for money; she asks him where he’s going, but she doesn’t ask to go with him. These are very Amarillo traits.

I don’t think Dylan was describing Amarillo’s particular problems. That’s not a Dylan move. But it puts me in mind of what was happening in Amarillo in the 1980’s. Oil billionaire, T. Boone Pickens, was picking fights with the local newspaper and the local university. Professors at the university were running an underground press, printing secret pamphlets that decried the billionaire’s corruption of the education system. They ran off the university president who was Pickens’ patsy. Pickens threatened to, and eventually did, pull his name off the College of Business. Eventually he ran the newspaper’s editor out of town, then relocated his own Mesa Petroleum to the metroplex. In a last jab, he said, “It’s easier to get people to move to the moon than Amarillo.” The downtown economy finally dried up, the result of decades of attrition and big moments like the farewell of the airforce base, the oil bust of the seventies, and the interstate cutting traffic off from the wealth of the suburbanish, burgeoning southern side of town.

There’s been a lot of optimism in Amarillo in the last few years. Downtown restoration, a wildly successful baseball franchise, new buildings all demonstrated that we were climbing out of the crater. Energy crackled like a streetcar wire, and a crowd was waiting at the stop to see if Bob Dylan would step down onto the sidewalk.

Now I’m just wondering where in the world Alicia Keys could be.

I’ve been listening to Billy Joe Shaver and reading James Joyce

Everyone knows Bob Dylan is important, but he’s operating on such a broad range of references–he places Anne Frank next to Indiana Jones– that sometimes it can be difficult for a person to enter his work. Ergo Alan Jacobs, who has written some of my favorite non-fiction books, especially “How to Think: A Survival Guide for a World at Odds.” In the lastest issue of Professor Jacobs’ newsletter, he paints the underlayers of Dylan’s latest album. He doesn’t reduce it with academic footnotes. He’s the generous teacher that draws your focus around the canvas of a master, then trusts us to draw our own conclusions.

In fact, if you’d like to read a history book that I can only describe as Dylanesque, I’d recommend Dr. Jacobs’ “The Year of Our Lord, 1943.” I don’t think I’ve ever read anything quite like it. He weaves T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, C.S. Lewis, Simon Weil, and a litany of other important and otherwise unconnected thinkers as they try to predict what society will look like if the war ends.

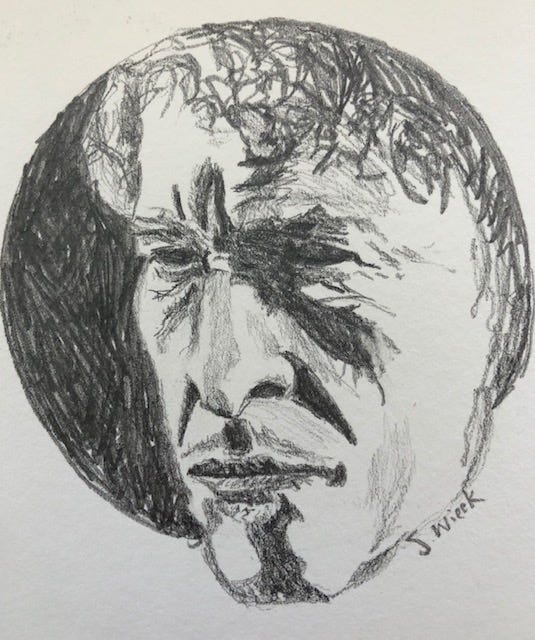

Something I Wrote

Millet’s L’Angélus

For David

The air distends, diffusing light and sound.

Our vespers announce on bellsong. Crows rise

in temerous peal of wingflap, feather-

flushed messengers, evangels and vandals.

Our heads lean in, prayer prone, twin candle-

flames bent on breath—whence it comes—what breather

gutters our thoughts, then on throatwicks, gives words rise:

According to thy word. A shaped sound, round

as a potato. These tubers never die,

but sprout eyes and live their lives beneath the ground.

The same bent back forks potatoes for the basket

and spades the hole for the casket of a child.

Should you have the chance, look up the history of the painting. Since my friend David Ritchie introduced me to it, the image has seemed downright providential to me. Also, I made up the word “temerous.” It’s ok. I’m an English teacher.

I’m Seth Wieck. Thanks for the company. If you like something here, let me know. Or better yet, let someone else know. If you hate something here, let me know. We might be able to come to an agreement, although I can’t promise anything.