Issue #17 - Stories Will Feed the People

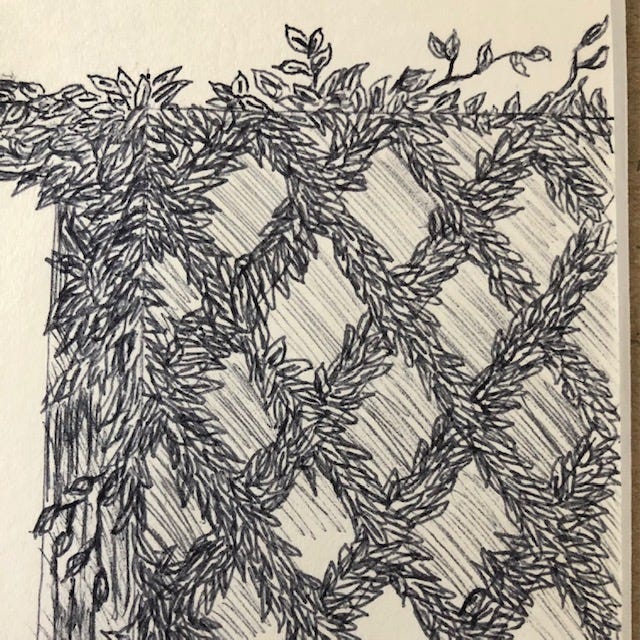

Twenty-two years ago, I picked up a Bic ballpoint pen and began drawing thousands of leaves growing on a trellis. I became obsessed with it. It also allowed me to process a lot of angsty teenage emotions in a way that my limited vocabulary wouldn’t have permitted.

Joyce Again

I told the joke back in Issue #5 about my college professor who’d drink two glasses of wine before he read James Joyce. The man spoke three languages (that I know of), walked the halls mumbling snatches of Goethe in German, and yet Joyce still intimidated him.

Not too long ago, we hired a man named Josh to build some fence for us. He grew up on a ranch in New Mexico, then joined the Army and spent time in Afghanistan. He sells feed to ranchers now, but for a few weeks he was in our backyard fencing our garden. He came in one evening and we had a beer and he saw my copy of Finnegan’s Wake on my bookshelf. Josh cracked a similar joke as my old professor, but he preferred whiskey.

We all three knew there was something that might nourish us within the pages of Joyce, but it remained inaccessible to the common man.

Over the summer, Dr. Bonnie Roos of West Texas A&M University (my alma mater) offered a free course teaching Ulysses over Zoom. The discussion was wide-ranging and extremely helpful.

However, as the conversation progressed, Dr. Roos voiced a universal concern of all humanities teachers: Does what we do actually matter?

I’m paraphrasing her spontaneous comments, but her effect was, “I’m envious of my colleagues in the agriculture and engineering departments. I hear the ag teachers say, ‘Our students will leave the university and feed the world!’ But where do the literature teachers add value? Maybe during a pandemic people are glad to have a few books around.”

She was presenting her own position as the strawman argument to make a larger point in the conversation, so I’m not holding her feet to the fire. But I sympathize. One of my freshmen students told me, “English classes just make me better at watching Netflix.” We don’t watch TV in my class, but we closely read stories of all kinds. Yet if all I’m doing is making my students more voracious consumers with persnickety appetites, then I should quit and get a job at a meat packing plant.

We are fundamentally noncognitive, affective creatures. The [end] to which our love is aimed is not a list of ideas or propositions or doctrines; it is not a list of abstract, disembodied concepts or values. Rather, the reason that this vision of the good life moves us is because it is a more affective, sensible, even aesthetic picture of what the good life looks like. A vision of the good life captures our hearts and imaginations not by providing a set of rules or ideas, but by painting a picture of what it looks like for us to flourish and live well. This is why such pictures are communicated most powerfully in stories, legends, myths, plays, novels, and films rather than dissertations, messages, and monographs. - James K.A. Smith

I read Jamie Smith’s Desiring the Kingdom in 2011, and then reread it several times over the years. Several of my friends read it at the same time and the ideas about imagination, desire, and perception became a parlance among us, so much so that I forget sometimes where I first learned the ideas. Smith became the editor of Image Journal last year and last month he wrote this editorial statement about James Baldwin, which reminded me how grateful I am to have read that book a decade ago. Read his editorial statement:

Healing the Imagination by James K.A. Smith, editor of Image Journal

Toward that end, my friend Dr. Ryan Pennington runs the Refugee Language Project here in Amarillo. At one time, Amarillo had the highest per capita refugee population in America. He’s helping disenfranchised groups of people connect to our community and learn English. It’s a bright source of good.

Anyway, he posted this about a Burmese-Myanmaran refugee named Jerry who works at a meat-packing plant, is learning English and earning his GED, and is a talented artist.

I’d like to be more like Jerry.

Something I Wrote

Laurence Musgrove at Angelo State University is managing a quiet little project called the Texas Poetry Assignment, full of regional poets and journalists. He published these two of my poems the week of the Presidential Inauguration.

There’s a Special Providence

When Our Dust Was Given Skin

I am no politician’s acolyte; they’re public servants not saviors. I catch some heat in private conversation when I say that I couldn’t care less about national politics. That’s not a true statement, but the tense conversations in which I claim my ambivalence usually leave me no room for nuance. Those conversations demand my total wide-eyed attention to the firehouse of information being created by national elections. But as Mary Oliver said, “The beginning of devotion is attention.” Forgive me if I am unwilling to develop devotion for those people whose only interest in my community is the exploitation of our devotion and resources.

Finally, a parable from Tolkien. I read it to my kids this week. I’m grateful for it.

“Leaf by Niggle” by J.R.R. Tolkien

I’m Seth Wieck. Thanks for the company. If you like or dislike something you’ve read here, feel free to respond to the email. I’m happy to keep the conversation going.