A few years ago in a neighboring town, which was booming as a safe alternative to my city, a man with no criminal record drove into the parking lot of a gas station and tried to steal a little girl at gunpoint. The girl’s grandmother intervened. The man shot and killed the grandmother.

Undaunted, the man fled the murder into the quiet suburban town and kidnapped another girl from her front yard. As a police chase ensued, the girl leapt from the car, sustaining only minor injuries, and the police killed the man in a shootout.

His family issued a public apology. Grasping for reasons, they explained that he had missed a few days of his behavior medication. They were as shocked as anybody and were grieving the loss of their father and husband and baffled at the latent evil that had resided in the person they loved. My news anchor cousin stopped by our house a few days after the story had blown over, and we talked about the giant questions looming over the whole ordeal. Why does this happen? How does this family wake up tomorrow? I’ll say this: be glad the news leaves out some details. We don’t let our kids play in the front yard anymore.

After that, my wife also refuses to watch movies that portray kidnappings. Most of those movies end well enough, but the dark fact heightening the tension in those stories is that in real life there are a lot of headlines about children lost, but very few headlines about children found. That fact has taught me the creaks of my house at night and how quietly my kids sleep. Those movies that end with the happy restoration of a family, with the perpetrator dead, with the community in balance again never portray the continuing ripples of threat or counseling or rent illusions of security—those movies provide saccharine comfort. A comfort that probably tastes much like our remaining ignorance at the end of a news broadcast.

In the midst of this, I still have the lingering belief—no, belief implies something I’ve conjured—I still have the lingering orientation, yes like metal shavings around a magnet, that stories can provide real comfort; as real as can be offered in this world, anyhow. Some stories succeed and some stories fail. What is the difference?

That may be a larger moral question than I’m capable of tackling here, but perhaps I have room for categories that provide some help in that direction. When I was in college, Sean Penn directed a movie called The Pledge. The film begins on the eve of a detective’s (Jack Nicholson) retirement. A little girl is murdered, and the crime has the tells of a serial killer. It’s a small town and the police pin their suspicions on a mentally handicapped man (Benecio del Toro). They interrogate their suspect so aggressively that he begins to believe that he did commit the crime. He confesses and then shockingly commits suicide in the police station.

For the law, at least, the case seems to be solved. Jack Nicholson’s detective, however, doesn’t believe that the mentally handicapped suspect was the real killer. He pledges to the girl’s family that he will find the true murderer even after his retirement. Over the next few years, as he alienates his former colleagues with dead-end leads, he becomes desperate to make good on his pledge and prove that his life’s work was meaningful. Finally, and horrifically for the audience, he befriends a woman and her daughter and uses the girl as bait to draw out the serial killer. The movie ends tragically with the old detective, completely ostracized, having become the kind of monster he wanted to stop. One of my professors praised it for its unflinching appraisal of real crime. I’m not so sure.

The Pledge is intended to be tragedy, and tragedy is meant to be cathartic, to purge us of our bad emotions, like pity and fear.

When I was a boy, my dad was hunting doves. Late in the day, he observed the birds along a fence line eating the berries from a plant and thought, “The birds surely know what is edible and what isn’t.” So he tried the berries. Within a half-hour, he was vomiting and hallucinating. His brothers put him in the back of a pickup and raced him to the hospital where the doctors gave him charcoal tablets and crossed their fingers as he continued puking black purge. Somewhere in the night, he turned a corner and survived. After some research, a game warden concluded that Dad had eaten something called snow-on-the-mountain. It’s deadly for almost every kind of animal except doves.

Catharsis—purging by story—is historically a noble aim for storytellers with roots at least as deep as ancient Greece. A culture, primed emotionally by real life conflicts, might gaze into a tragic story and enter the maws of hell and be spat back out, purified and reborn—or if art fails in this medicinal role, simply be shocked and repulsed. But I have to say, the entire cultural project of the Greeks, the direction in which all of those stories aimed, seemed to be tragic. Even the heroes die and become shades longing for any sort of life over the anhedonian wandering of the underworld. “Better to be the hired-hand of a farmer than dead,” said famous Achilles. The purging Greek stories offered was only a mild nihilism in preparation for the ultimate nil of death. Anyhow, I’d like to think I have the stomach of a dove, but most days I’d suffer the indigestion of a cloying comedy over the retching of a bitter tragedy. My orientation still suggests these are not my only options.

An editor once accused me of being like William Blake. I say accused because I don’t know what he meant by it, so I took it as accusation. But Blake offers something helpful along our lines. In his Songs of Innocence we find a set of zygotic poems: “Little Boy Lost” and “Little Boy Found.” All of the Innocence songs are narrated by a child, and so in these poems we hear a boy who has become lost calling after his father. The implication is that the boy dies, but since the narrator is a child, this is not explicitly stated or even understood. Death for a child, although real, doesn’t carry with it the weight of memory and stewardship. Flip the page to “Little Boy Found,” and in eight lines the child is found by a new father, God, being “ever nigh,” and led to his mother who preceded him in death. A new and holy family. This is comic—as in, things end well despite the terrible circumstances—but it isn’t cloying because the narrator is innocent. He did not experience the ongoing grief, and we aren’t privy to it either.

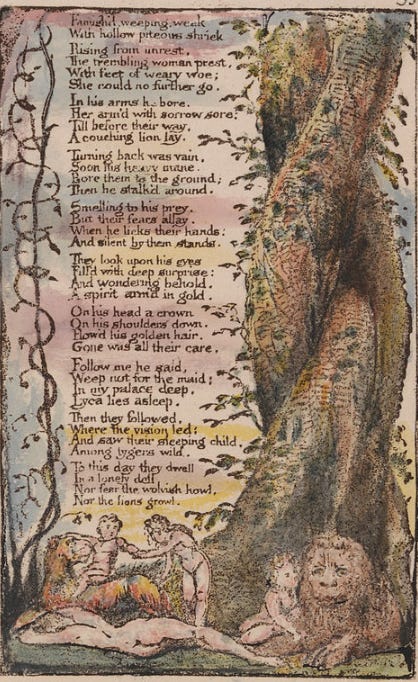

These poems have their twin, or perhaps their older self, in Songs of Experience, beginning with “Little Girl Lost” about a seven-year-old girl named Lyca who has gone missing. The narrator here is decidedly more adult, sympathizing with Lyca’s parents and voicing the community’s disbelief at the death of a child:

How can Lyca sleep

If her mother weep?

Death has gravity now, for those survivors who must continue suffering in the grief that must only grow and pull and slow the passage of time, delaying our escape to relief. Why doesn’t the exertion of our grief restore the one we lost?

The title of the second poem, “Little Girl Found,” might suggest Lyca’s miraculous restoration. She’s found! Maybe she simply fell asleep beneath a tree, awaking no worse than groggy, but found and in a lot of trouble. But instead, Lyca’s parents suffered the real and final loss of their daughter. The poem recounts how the parents spent the remainder of their days searching for their daughter in deserts and valleys and are eventually slain themselves, in their search, by a lion in the road. This would be tragic, maybe the perspective of Experience, except that the poem opens like this:

In futurity

I prophesy

That the earth from sleep…

Shall arise, and seek

For her Maker meek.

The parents are awakened from death by another lion, a king, presumably God who leads them to their daughter. A restored family, no doubt bearing the ripples of their suffering, but the poem ends with the family

not fearing the wolf’s howl

nor the lion’s growl.

No longer will this girl or her family or community lose sleep over the potential dangers lurking in their neighborhoods.

Prophecy has looked different in various cultures. The Old Testament prophets will never be called saccharine, but I don’t think they can be called tragic either, even if as many of them were called to tragic vocations; ignored and misunderstood by their audiences; slaughtered by the people they served. On that level, they were like their counterparts in the Greek prophets, Cassandra and Tiresias. But the Tiresias we met warning Oedipus, we ultimately find lapping goat’s blood in Hades alongside Achilles. Hell didn’t spit him back out. It consumed him. All that remained was smoke and a nostalgia for the blind man’s heat. The stories of the Old Testament prophets aimed at something different, stoking imaginations against the nil-fates of the ancients, finding their cultural fulfillment ultimately in a man who charged through death, clamping the jaws of hell, brandishing a light that sent darkness cowering. Stories can be after that.

These are the stories in which I keep imagining myself, anyhow. After all, I am a husband and a father, foolish enough maybe to bring children into this gaping world. And more hauntingly, against the tragic potential latent in my own desires, I am a father with no criminal record or history.

— This essay was originally published at Curator Magazine in June 2013.