If you’ve been reading In Solitude, For Company for a while, then you know my wife, Katie, is not a “literary” person. That is not to say she isn’t smart; she’s just American busy. She’s the broker of a real estate company. She manages employees and thirty agents, rental properties, and sub-contractors. It’s not unusual to see her put on a tool belt and fix things herself. When she was in labor with all three of our kids, she took phone calls from clients between contractions. So after a day of work, her first inclination is not to reach for a book. And if she does, she isn’t going to analyze a book for themes and meanings.

However, a few years ago, she did pull John Steinbeck’s East of Eden off my shelf, and in three days devoured the Nobel laureate’s most important work. As is appropriate after turning the last page of a great book, she spent a week in a daze. The world around her had changed, as if the narrator now sat on her shoulder telling her things to see that previously would have sank beneath her attention.

Still, Steinbeck sometimes drifts from plot into painterly descriptions of flora, fauna, and landscape. American Busy Katie skimmed those sorts of passages, looking for the next paragraph that contained details about the Trask family. A few days after she finished reading, she turned to me in bed and said, “What does ‘timshel’ mean?” In her skimming, she’d missed where Steinbeck placed “timshel” early in the story and so was confused when the book concluded dramatically on that word. But Steinbeck had done such a thorough job leavening the story with the word’s meaning—yes, even in his description of flora and fauna—that it was almost unnecessary to include it explicitly in the text. Katie understood the meaning of the story on some subliminal, sub-language level even if she missed one key moment in the story.

In Mystery and Manners, Flannery O’Connor’s collection of essays about writing fiction, she declares

When you can state the theme of a story, when you can separate it from the story itself, then you can be sure the story is not a very good one. The meaning of a story has to be embodied in it, has to be made concrete in it. A story is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the story to say what the meaning is. You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate. When anybody asks what a story is about, the only proper thing is to tell him to read the story.

O’Connor was a queen of sharp rhetoric. Declarations like that leave a puncture wound. It’s easier to apply pressure and nod your head than it is to argue with her. That is until you read one of her stories and realize that she crammed them full of symbols and allusions and themes. Why put them there if you don’t want us to find them and sort them out and examine them in pieces?

I’m not sure Katie would find those literary elements—themes, symbols, etc—because she isn’t trained to, but literature classes can sometimes over correct. Take O’Connor’s story A Good Man Is Hard to Find for example. When asked about the symbolic importance of the villain’s black hat, she famously quipped, “It’s hot in the South. He needed a hat.” Whether my wife realizes that the grandmother in that story falls dead in a cruciform posture probably doesn’t matter. Emotionally, the story does its work.

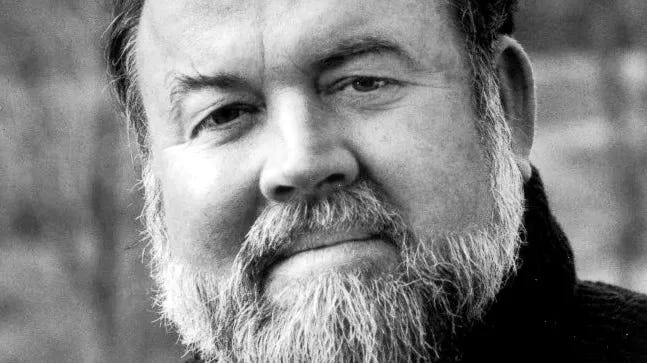

In 1986, an interviewer from the Catholic America Magazine asked Andre Dubus if Flannery O’Connor had influenced him.

“No,” Dubus said. “She frightens me….I wish I had never read that quote of hers where she said that she writes about sacraments that nobody believes in. Every time I read her stories….I’m looking around for baptisms and Communions.” Then knowing that he’s being interviewed for a Catholic magazine, he concedes, “I have a story, ‘Miranda Over The Valley,’ which is full of Catholic symbols and allusions, and yet few have mentioned them in critiques of this story. On the other hand, I hoped nobody would because they were for me.”

Why would Dubus hope that critics would miss the Catholic symbols? By all accounts, Dubus was openly Catholic, unconcerned about how that would affect his reputation among the literati. Why then did he hope that the Catholic figures would be overlooked “because they were for me”?

On its face, there is nothing Catholic in “Miranda.” There are no churches and no priests, the characters have no Christian practices, no prayers, no Bibles, not even a lingering piety on religious holidays. Jesus is invoked many times but only as a vain interjection!

The story opens with the 18-year-old virgin Miranda—full of earnest passion and emotions—about to make love to her boyfriend Michaelis the night before she flies across the country to attend college. Michaelis seems like a good, young man. Her parents approve. He works a manual labor job while preparing for law school. He treats her with respect. They make love and the next morning and first month of college, she’s in the most delicious love with Michaelis. In contrast, her roommate Holly has sex with multiple lovers, including a weekday guy named Brian who shows no signs of commitment to anything in life (he’s six years into college) as well as a weekend guy named Tom who has husband potential. Seeing her roommate’s behavior only clarifies her bond with Michaelis. She tells Holly that she can’t imagine sleeping with anyone else. “I’d feel divided,” she says.

The pure happiness of her love, though, begins to give way to fear as she misses one period and then another. On Halloween, she visits a gynecologist and sure enough, she’s pregnant. Michaelis takes the news like a man and begins making arrangements for a wedding. Her fear begins to fade because she’s bound to Michaelis in love. Miranda flies home and her parents and Michaelis have a conversation about what keeping the baby would mean for the rest of their lives. Even though she doesn’t ask for it, or even want it, her parents give her permission to have an abortion. She sees the relief in Michaelis’s face. Her parents bribe them with a honeymoon in Acapulco. In the end, she concedes to the abortion because everyone else in her life has abandoned her desire to keep the baby. The rest of the story demonstrates how all of her relationships, innocence, and trust are ruined. She sleeps with Holly’s weekday guy, Brian, and feels herself being divided into four separate Mirandas.

Now, what damage have I done to the story even by summarizing the plot? In literary terms, plot is merely one element like diction or character or setting. Further, because most people in our country have baked in political beliefs about abortion, the mere mention of it divides my readers into camps. Rather than experience the humanity of the story—characters having to make hard decisions in tough situations and deal with the consequences—readers of my summary might be tempted to jump out of the story and find out which camp Dubus aligns with. It’s like taking a spoonful of baking powder out of the pancake mix and saying, “Here taste this. This is the pancake.”

By the way, actual life is not so neat as to be separated into elements. That’s one of the reasons I like reading fiction. Better than a non-fiction argument, stories put me in the position to make decisions and suffer or enjoy consequences while I live with the characters.

In another interview in 1986, this time for a secular literary review, the interviewer presses Dubus to divulge some of the Catholic elements he placed in the story.

At key points in this story, people say “Christ” or “Jesus”—and why they do that is my own little secret. To me, these words are prayers. She finds out that she’s pregnant on Halloween…and flies home immediately. So later, on either All Saints Day or All Souls Day, she is convinced to get the abortion which she doesn’t want.

That’s it, there’s the baking powder. We could do a little theological work with the significance of aborting the baby on All Souls Day. The cloud of saints throughout history, including the martyrs who suffered, stand as witness to the death of the innocent, welcoming the babe into the train of the dead. But because the characters have no faith, the narrator is confined to just telling what happens in the room. If the reader is aware of the church calendar, then the significance rises—there’s the leaven—but, as Dubus said, these moments in the story were for him as he wrote it.

He wrote the story because he was horrified by abortion, largely because Catholic teaching. He was wrestling to find the humanity in a person who has an abortion, and all of the relationships and social forces that lead a person to make a decision against her conscience. Those elements of Catholicism throughout the story were there for him to keep going, to allow Miranda to become a human and not a pasteboard character against whom he could spit agitprop. He continues in the interview

[The story] was so hard to write. I started every fall for years and couldn’t finish it, I had to try to get myself out of it and not preach. And Miranda finally took over very well. As a matter of fact, I wrote the ending over several times because she was so hard at the end and I didn’t want her to be so hard.

Sometimes, I see Katie’s eyes glaze over when I start picking out story elements. I’m insufferable while watching TV. However, it’s a discipline I have to maintain as a writer, and again a spiritual discipline I need to maintain as a Christian. How to love people I might find as my enemy? The story elements are hardwired in us to see humanity stand up on the page, to come alive in the hearts of the reader so she sees the world anew.

Reading stories is a way to love the world because God so loved it. Afterall every few days or weeks or years I wake from a daze with a word or image on my mind and think, “What does this mean?” and I’ll set off on another story to find out.

Story Published

The fine folks at Solum Press published, or rather re-published, one of my short stories in their Winter 2022 issue. The story was originally published at Narrative Magazine in 2011, but I figured it had been over a decade since it came out. It was the first story I ever had published, and I think it captures a whole lot of what I’m hoping to accomplish with stories. You can read it by clicking the button below.

It's funny- I've never thought of that being the difference between fiction and non-fiction, that journey you go through with the characters, emotionally invested and part of their lives. But I realize now it's because my favorite types of non-fiction are blended, poetic storytelling that just happens to also be true. The Soul of An Octopus by Sy Montgomery is one of my favorite books to this day. But I'm still lost in the story with her, meeting octopuses and going scuba diving and learning about aquariums because - that's what I do when I'm interested in something... I deep dive. She and I are the same and therefore are on the journey together. And so it doesn't feel like yucky boring non-fiction :) to me. But it's the storytelling, the soul bearing. That's what drives me to it. There's nothing like good writing, storytelling, poetry. It just hits different. Sending love to you and Katie <3 Hug her and the kids for me.

This is absolutely one of my favorite topics, and you handled it so well! Bless Katie and all others who read and are changed without analysis. I'm not suggesting that I dislike literatary analysis. In fact, I love it, but as T S Eliot said, genuine poetry communicates BEFORE it is understood.