Cormac McCarthy died on June 13, 2023. If you’re the literary type, this isn’t news to you. But even if you’re not literary, you may be aware of his books All the Pretty Horses, No Country for Old Men, and The Road. There are many people who are more qualified than me who have written fine obituaries, so I’ll leave it to them and be grateful they wrote them. I personally try not to analyze McCarthy’s works too closely, though they have been my steady companions for twenty years. I’ve seen some people rigidly dismantle his fictional worlds into gears and pulleys and themes and ideologies and the life drains away and you’re left with a dead, cold planet spinning silently in space.

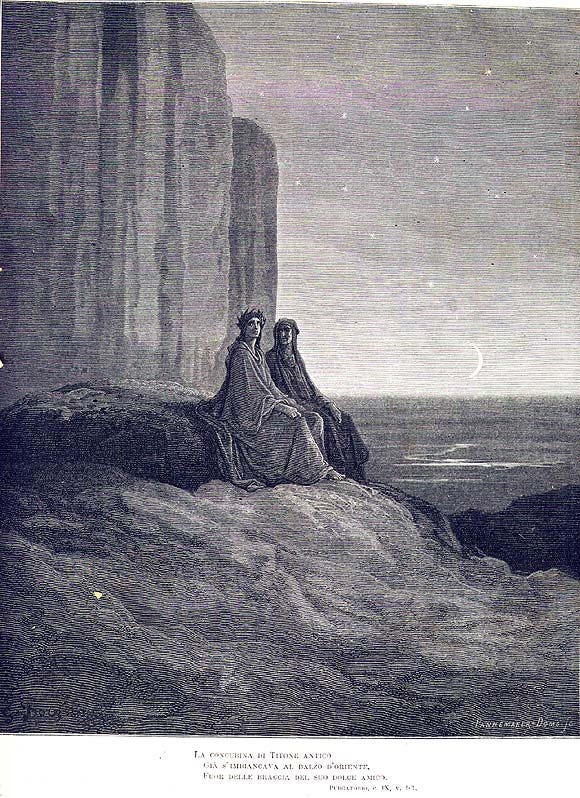

But if you read him long enough, and read things he must have read too, then it’s pretty safe to say that McCarthy saw himself as a type of Virgil, the ancient Roman poet. Besides writing The Aeneid, the epic poem that established the mythology of the Roman empire, Virgil also became an influence on every civilization that followed Rome. Constantine quote Virgil when he converted Rome to Christianity. Dante chose Virgil to guide his pilgrim through Hell and Purgatory. His phrase E Pluribus Unum was first stamped on a U.S. coin in 1795. In short, one could say that Virgil played a major role in what we call Western civilization, and Western civilization is a fragile thing always under threat by the products of its own making: war, famine, conquest, plagues.

One of McCarthy’s most famous books is Blood Meridian, which is subtitled The Evening Redness in the West, and certainly reads like an apocalyptic end of civilization. The protagonists of his final book The Passenger/Stella Maris are surnamed Western and are the children of scientists who developed the atomic bomb. The end of Western civilization is on his mind.

It’s worth looking back to Virgil from our end of history. What did he see then in our beginning?

As continental Europe descended into World War II, the Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh described a rural land dispute of local concern in his sonnet “Epic.” A farmer, standing on a hill, defends his right to a plot of land by waving a pitchfork at his encroaching neighbors. Across the Irish Sea, the world may have been mad for a global war, but the parochial Irish poet concludes,

Homer’s ghost came whispering to my mind.

He said: I made the Iliad from such

a local row. Gods make their own importance.”

At the beginning of Virgil’s The Aeneid, the great city of Troy is in flames. After a ten year war, the Trojan walls were finally breached by the resourceful Greeks, and scenes of carnage are on display in every street. Men are butchered before their families, infants are thrown from walls, women are corralled and doled out among the invaders. The once glorious civilization has reached its Armageddon. Aeneas, the greatest remaining warrior, is determined to die defending the city, but instead is visited by the dead Trojan prince Hector in a vision. And what does the shade of Troy’s noblest prince command? “Troy trusts its penates to you. Take them to share your fate, find room across the sea to build high walls for them again.”

Penates

Penates, in Latin, can be simply translated as “household gods.” In her version of The Aeneid, Sarah Ruden translates nearly each of the twenty-plus occurrences as such; Allen Mandelbaum included in the notes to his translation that “Penates are household or family deities, or gods of the state considered as a household.” These are not the Dii Consentes, or the council of the twelve major gods. These are smaller gods who are never named in the Aeneid and who are forgotten to history, yet their statues are saved from the burning city. Famously, pious Aeneas asks his father to carry the “penates” because his own hands are so covered in battle gore that he would dishonor the gods to touch their statues.

William Barker provides a more thorough understanding of “penates” and the intrinsic meaning they would hold for a community of people.

The Penates were divinities, or household gods, who were believed to be the creators and dispensers of all the well-being and gifts of fortune enjoyed by a family, as well as an entire community…It is not clear which of the gods were venerated as Penates…but every family worshipped one or more of these, whose images were kept in the inner part of the house.

And according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “‘penates’ means the ‘gods of the inside of the house.’ It’s related to the Latin penatus ‘sanctuary of a temple’ (especially that of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth), and cognate with penitus ‘within’ where we get the English word ‘penetrate.’ ‘Penates’ presided over families and were worshipped in the interior of every dwelling.” In other words, “Penates” represented the smallest scale of religious devotion. These were the local gods, worshipped by families and cousins, and maybe the small surrounding village.

In October 2022, Dr. Emily Wilson, who translated The Odyssey and The Iliad, tweeted, “I went to Troy….It’s amazing how much is there, and how little. The scale is so small, yet so many layers of history and stories.” Both Dr. Wilson and Patrick Kavanagh understand that the gods of Troy were not the mighty gods of empire. These were the gods of a man defending his land with a pitchfork, not in a condescending sense, but in the sense of scale. The empire gods will demand more and more allegiance, will pull our devotion from our hearths and villages toward an abstract capital city. Living during Rome’s transition from representative republic to authoritarian empire, Virgil understood this as well. His use of “penates,” his hearthgods show it.

The first use of “penates” in the Aeneid comes in the voice of Juno, one of the Dii Consentes—the empire gods— and she refers to them belittlingly as “Troy’s beaten gods (victosque penates).” But as the story allows Aeneas to narrate the events, he refers to the “penates” reverentially as the household gods, and he keeps them safe through shipwreck; he brings them again when he leaves Carthage, and to the city of Acestes, a city that promises to be like Troy; small and with the same customs. But in Book V, while the harried Trojans find a bit of respite, Juno sends her handmaiden Iris to belittle the Trojan gods, disguised as a Trojan woman. “Penates we saved from war for nothing!” she screams. With this agitation, Iris convinces the women of Troy to burn their ships.

Interestingly, after the flights, deaths, and burials of Books I-V—and eleven references to “penates”—the word is abandoned in Book VI in preference to “deos” or “deus” which no longer have the small, local connotations of the household gods, but the Dii Consentes. In the most dramatic scene in the Underworld, the oracle Sibyl—possessed by the voice of Apollo—prophesies that Caesar Augustus will erect a temple to Apollo:

Troy’s fortunes must not dog us any farther.

All of you, gods and goddesses, who balked

At Illium, the splendor of our reign,

Can spare us now…

…let the Trojans settle

In Latium with their wandering harried gods (deos agitataque).

I will decree a marble shrine for Phoebus…

…Feast days

Will have Apollo’s name.

To step out of the story for second to realize that Virgil, writing in the time of Augustus, has Apollo, the empire god, “prophesy” that the emperor Augustus will build a temple to Apollo. Virgil isn’t prophesying anything; he’s simply describing what has happened.

Before Virgil composed The Aeneid, he spent several years penning The Georgics, a didactic poem that was ostensibly about farming methods and bees. When it was completed, Augustus invited him to Palatine Hill and Virgil spent several evenings reading the poem to the new emperor. The poem, comprising four books, uses a variant of “penates” only twice, and in most English translations it is almost always rendered as “homes” or “hearths.” The context for each use is enlightening, and I think, intentional on Virgil’s part, so I will quote them at length.

Happy is he who knows the rural gods, Pan and aged Silvanus and the sisterhood of Nymphs. Him, no honours the people give can move, no purple worn by despots, no strife which leads brother to betray brother; untroubled is he by Rome’s policies spelling doom to kingdoms; he has not pitied the poor, nor envied the rich. He plucks the fruits which his boughs, which his willing fields, have freely borne; nor has he beheld the iron rigours of the law, the Forum’s madness, or the public archives. Others brave with oars seas unknown, dash upon the sword, or press their way into courts or chambers of the kings. One wreaks ruin on a city and its wretched homes (penates), all to drink from a jewelled cup and sleep on Tyrrhian purple.

In this instance the empire’s unlimited ambitions ruin the small household gods located on the provincial edges of the empire to extract their wealth. Virgil recommends the happiness of the farmer, the worshiper of small, rural gods, but the subject keeps drifting to the workings of the empire, and the men who throw themselves into strife for silly rewards—to press their way into courts and chambers of the kings. Even though the small household gods are forsaken and ruined out of allegiance to the empire’s deities, it does not translate as happiness for those in the capital city.

The one other use of “penates” in The Georgics portrays a contrasting, happier scene in the life of bees.

Come now, the qualities which Jove himself has given bees I will unfold…They alone have children in common, hold the dwellings of their city jointly, and pass their life under the majesty of the law. They alone know a fatherland and a fixed home (penates), and in summer, mindful of the winter to come, spend toilsome days and garner their gains into a common store.

The bucolic life of bees is compared to the bustling scramble of men, and what do they have that the men don’t, besides happiness? Penates, fixed household gods, dwelling in the deep recesses of their homes. The bee citizens are happy, working hard for their communal life.

By the end of the Aeneid, Virgil has abandoned the term “penates.” It does not appear once in Book XII. Again, like in the Underworld, he only employs “deos” to refer to gods, most notably in Jove’s speech to Juno, convincing her that the old gods of Troy will cease to be worshiped.

…The Trojans will fade out

As they breed in. I’ll introduce new rites,

But make one Latin people, with one language.

You’ll see the new race, with Italian blood,

Surpass the world—and gods—in piety.

Nobody else will bring you greater worship (Ruden)

Robert Fitzgerald renders it: “You shall see—no nation on earth will honor and worship you so faithfully.” The transition from the small, local, and parochial worship is complete. The federal council of the empire gods now demand worship from the provinces.

Often in his life, Virgil attempted to leave Rome and return to his family land—which had been confiscated by the empire—in Mantua to live in peace. Over and over again, he was required to return to Rome, away from the hearthgods of his family and the communal life that formed him.

Now that Cormac, our Virgil, has passed away, remember the penates, the hearthgods of our beginning.

Seth, you are amazing. What a fascinating trajectory from Cormac McCarthy to Virgil. May the house gods continue to bless you. My very best, Carol