I’d like to thank the Friends of the Cornette Library for indulging me as I told a few stories about my experiences at the library. If you grow up in a small town, you develop a kind of physical memory of a place. Renea Dauntes, the outgoing chair of the Friends told me I could talk about whatever I wanted, which is a dangerous proposition in these times. I was a little surprised that got emotional while giving the speech at a luncheon.

Originally delivered on April 23, 2024:

These stories might seem disjointed, non-sequiturs as I tell them, but I aim to draw them all together. The wise teacher in the book of Ecclesiastes admonishes his son: Of the making of many books, there is no end. But I think I’ll make an even finer point, paraphrasing Hamlet, as he paraphrased Christ: there is a certain providence in the fall of a sparrow. Yes, and a certain providence in how a book finds us.

As you all know, the Cornette turned 50 this year. I’m 43 so the library was only 7 years old when I was born in 1981. I try to imagine what it must have been like in Canyon then. If you were to drive down 4th Ave, west to east, you’d pass the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum, erected in 1932. Art-deco flourishes, eagles on the cornices, and engraved reliefs of longhorns and cowboys and Plains Indians, antelope, and jackrabbits. Then the museum swings away and the campus opens up and you look down the elm-lined lane at the perfectly symmetrical, classical Old Main. The stalwart flagship building of WT since 1916. There’s no mistaking that this is a serious college campus when you see Old Main.

But then the century progressed. There was an arms race. A cold war. A race to space. It’s 1974. The public has had enough of the Vietnam War, and public distrust for government spending has led to the rise of purely functional, utilitarian buildings. No more can we get away with extravagant embellishments on our government buildings. Now from 4th Ave, you peek over Old Main’s elegant shoulder and there is the new, hulking, brutal, Cornette Library. Long flat walls formed from conglomerate concrete with nary a window nor dimension, almost floating it appears, on its hidden, inset foundation.

Of all the buildings though on this campus, I have the most affection for the Cornette. It was the first building on campus that I ever stepped into when I was a child. My mother was an on again, off again student here, and we were able to check out books. My dad, a farmer and rancher, would often bring us up on Sunday afternoons after church to research agricultural journals, and my sister and I would be free to roam the grounds. The elm trees seemed like a forest to eight year old me.

Those Siberian elms are transplanted here from Russia. They were adopted early by the pioneers in the panhandle with nearly no native trees. I believe the thinking is that if it can grow in Siberia, then surely it can grow here. So most of the oldest trees in Canyon are elms.

The elm trees. In constant need of pruning. As you were walking in you may have noticed the piles of the yellowish-white seeds piled up on the sidewalks, in the edges of the grass, tracked in through doors, and plastered in the mud. In the spring it can almost look like snow being produced by the lately green canopies. These seeds are called Samaras. Little round disks, as if they were made of paper, millions of seeds, these samaras, on paper wings. Like envelopes delivering messages on the wind. What an extravagant waste. How many billions of samaras have fallen compared to how few trees have germinated, sprouted, and grown. It’s an incredible amount of energy elm trees expend in making their seeds, for virtually none to sprout. How does one tree plant itself and grow? This is beyond our control. If evolution and survival of the fittest favors efficiency, then elm trees seem bent on extinction.

That is one way in which to think about nature. Unless we take into account that these seeds cover the ground and immediately begin to decompose, adding organic matter to the soil in layers, enriching the ground they grow in. Add to that most of a tree’s mass is drawn from the carbon in the air, so the weight of even those seeds is captured from the wind that bears them, ensuring that the soil grows richer and richer over the years. The elm trees are thinking in hundreds of years, not about this spring’s crop of potential saplings, but hoping that the soil twenty years, fifty years, a century from now will have harbored and nourished further generations of elm trees.

I joked earlier that the Cornette doesn’t have any windows, but surprisingly, once inside the building, there’s an abundance of light. The window columns on the corners and the sky light in the atrium over the circulation desk welcome in brightness without giving away what time of day it is. The library is a place that exists outside of time.

Roaming outside often turned to roaming inside. Maybe I was looking for my parents, but mostly I wandered up and down the rows of books. If you run fast enough, looking sideways down the shelves of books, you can get the experience that you are merely flipping through the pages of a book, each row flipping to the next. And if your sister is running down the aisle at the other end of the row, you kind of get the experience that you’ve drawn a cartoon character in the corner of a book and as you flip the pages, that cartoon character moves. That’s frowned upon by the librarians though.

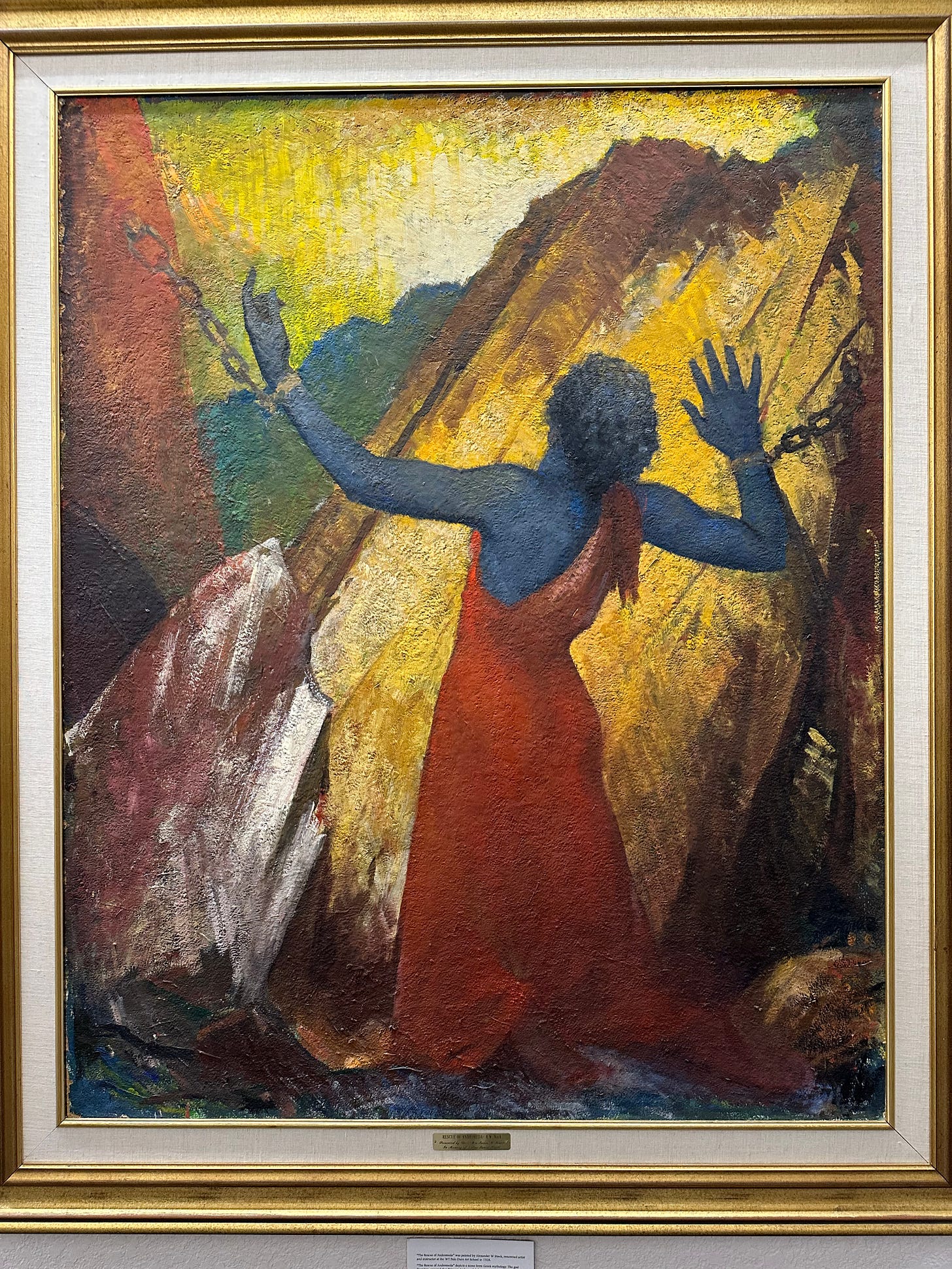

Once when I was fleeing a librarian, I turned the corner and froze. On the wall was The Rescue of Andromeda. A massive painting. It’s been in corners of the library over the years. I noticed it tucked up by the philosophy section lately. But in the center of the painting is Andromeda, her back to the viewer wearing a red dress. She’s chained to a wall of rocks, yellow I presume as the sun behind her, behind us the viewer, is setting and casting the whole cliff in the golden hour hue. And she is blue. Her blue skin doesn’t seem alien though. In the myth, she’s Ethiopian, so she would have been dark-skinned, but the painter is only working in primary colors. The first colors from which all the other colors are derived, much like those ancient myths, are the primary stories for our culture. The painting both terrified me and captivated me. It’s terrifying because the subject is a woman chained to a rock. We don’t even have to see the expression on her face to know that she must be terrified herself. But it’s also beautiful. According to the little brass placard, the painting is titled “The Rescue of Andromeda” so there’s some relief. She is being rescued, but there’s nothing in the painting itself that would indicate that is happening. She’s been chained to that rock since I saw her the first time when I was eight years old, and she’s still chained to that rock.

Greek myths are some of the first books I read here, so if you don’t know the full story of Andromeda, this is how the Roman poet Ovid described her rescue:

Perseus (fresh from having killed the Gorgon Medusa) strapped his wings onto his feet

And armed himself again with his hooked sword,

And with his swift-winged sandals split the air.

The world fell back away from him in flight

Till he saw Ethiopia beneath him

And near it, the kingdom ruled by Cepheus,

Where Ammon had condemned Andromeda

(the one unjust, the other innocent)

To pay the price for her own mother’s speech.

At sight of Andromeda, bound high upon a cliff,

He would have thought that she’d been carved from stone

Were it not for the breeze that stirred her hair

And for the warm tears flowing from her eyes;

The woman’s beauty quite astounded him,

And left him witless, to the point that he

Almost forgot to keep his wings in motion.

“Oh!” he said, “These chains don’t do you justice;

The only chains that you should wear are those

That ardent lovers put on in their passion.

But what’s your name and land of origin,

And why are you chained up?”

Eventually Perseus leverages Andromeda’s rescue for her hand in marriage. He kills the dreadful sea serpent, and then carries Andromeda off to be his wife.

Let’s consider the moment Perseus sees Andromeda.

“Bound high on the cliff, he would’ve thought that she’d been carved from stone…”

He almost passed her by, he’s running so fast past the granite cliffs that he almost doesn’t see her, BUT “the woman’s beauty quite astounded him and left him witless.” He almost forgets to keep flapping his wings.

I’ve often wondered why that painting is displayed here. What does a terrified woman, chained to a rock, about to be sacrificed to a sea serpent have to do with a library? The more I stand in front of that painting, the more I realize that I, the viewer, am standing in the place of Perseus. I had been running, moving so fast through the world, caught up in my worries and cares, that I couldn’t see what was there in front of me. And suddenly the beauty quite astounded me. Plato supposes that Beauty—capital B—exists as a perfect form, outside of our senses, but that occasionally it breaks through to us, and we witness it, and are moved to create something that attempts the form of beauty. I think that walking up and down the aisles of books, sometimes the spine of a book, back to us, astounds us. How does one book plant itself and grow? This is beyond our control.

I’ve seen nearly all of the books in this library. Or at least all the books that were here in the summer of 1998. I was employed for the summer by Jack C. Thomas & Son Paint Company. If you’ve been around long enough, then you know that the Cornette Library used to be avocado green and orange. In the summer of ‘98, we repainted everything beige. We re-lettered all the sign boards and restained all the wood work. By the way, take a look at every book shelf in the library. Each shelf has a metal end panel that was either green or orange. My friend Eran and I took each of those panels off, loaded them onto a truck to be sandblasted, and they came back beige for periodicals and maroon for loans. I stood in every aisle holding painters’ ladders and refilling buckets and cleaning brushes. While I waited at the bottom of ladders and scaffolding, I perused the books. I think I’ve seen the title of just about every book here. How does one book plant itself and grow?

We would take our breaks out on the loading dock, and the painters would tell dirty jokes and smoke cigarettes. I was making $7 an hour at 17 in 1998, and I thought I was rich. I bought a gold pocket watch at the end of that summer. One wise sage of a painter looked at me one day. He could fit a cigarette in the gap where his two front teeth used to be and he said, “You should probably go to college.” And I thought maybe he was right. And the library transformed into something new. No longer a place of recreation, but of vocation.

In the summer of 2001, I was selected to be a McNair Scholar. One of the goals of the scholarship was to spend about 6 months researching with a professor and writing a paper that we could present at conferences.

The question of my research was how do we, a culture, decide on a canon of literature. How do we pick, decide, agree on a group of books that have come from us, out of the millions of books produced each year, and we’ll say these books represent us as a people.

Do we begin with the ancient myths? I for one love them. Does Shakespeare make the cut? Why? Who says? The question was too big for a summer, so I narrowed in on Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Why do we still study Hamlet?

For my research, I read Derrida, Lacan, and Freud. Rather, I beat my head against them. I was 20. I had no background in all the other philosophers and history to make any sense of what I read. My goal for that summer was to read for 6 hours a day. I would make it about 30 minutes before I fell asleep in a book and dream and wake up and then read Freud interpreting dreams. I remember being so frustrated and leaving the desk to walk through the aisles like I had done as a kid. None of the philosophy stuck with me. I worried about the suitability of my brain for ideas to sprout. There more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than in all your philosophies.

And my brain rebelled. And how did I rebel against my studies. I was in a library. I wandered through the shelves. What happens when you stand in front of a bookshelf? Do you only see a wall of bookspines? The books I ran past as a kid. The books I stood in front of as a teenager. I was overwhelmed with the thought that people spend years of their lives making these books to fill these shelves, for most people to simply walk past them unseen. Unopened. Unread. A billion pages and a billion seeds on paper wings. What an extravagant waste. How does a single book ever make it off the shelf and plant itself in another person? Let alone a canon?

This question about the canon, about the books we choose, about the work of a library isn’t far off from the elm trees thinking of their soil a century from now.

One final story: When I graduated in 2003, I had the notion that I would become a poet. I was decidedly not going to be a philosopher. Not knowing where to begin, I would come to the Cornette on Saturdays and browse the poetry section. I’m not sure what led me to Dylan Thomas. (And death) There’s a certain providence in how books find us. Maybe I’d heard his name in my studies, although I know we hadn’t studied him. But there in 8 or 9 volumes of Dylan Thomas collections, were two copies of The Notebooks of Dylan Thomas, edited by Ralph Maud. The Paper Circulation card, from back when they used to stamp the books when they were checked out. I noticed this earlier, speaking of providence. The date stamped on the card says the last time this book was checked out was April 23, 1981. 43 years ago today when I was three months old, and now I’m here, telling you how I was quite astounded by the beauty of this book. There’s a certain providence in how books find us. Now I know for a fact that wasn’t the last time that book was checked out because I checked it out over Christmas in 2003. And then again about 10 years later when I wrote an essay about Dylan Thomas. I noticed again that there are still three strips of paper in the book that I used as bookmarks while writing my essay. My guess is I was the last two people to check this book out.

Now more specifically about this book: The Notebooks of Dylan Thomas. It covers 4 years of his development as a poet 1930-1934, between the ages of 16-20 years old. He had long stretches where he would write a poem a day. Most of them were not good; although, it’s easy enough to find a phrase or a line that shows the signs of his genius. A playfulness with language. In an interview when he was 19 or 20, he said “The laziest workman receives the fewest impulses; and vice versa.” It It’s an extravagant waste of words. Nearly none of those notebook poems became a poem. I can think of one exception. In a letter, he recounts working on a poem in his parlor when news arrives that his aunt is dying of ovarian cancer. He’s a teenager, caught up in his selfish ambitions. He has a difficult time knowing how to feel about the news, more concerned that he isn’t feeling a straight emotion.

Again he’s a teenaged boy. He’s probably never felt this emotion before. He tosses off a few ironic lines. But later, when he’s 23, he writes a beautiful memorial to her. He’s able to express real grief, through the music of language, because he sorted it out in those notebook poems. Was it a waste? Was it a waste that he taught me how to grieve, to learn how to grieve, and to make something beautiful out of it? How to join the long history of humanity? Was it a waste for that book to sit on the shelf these last 43 years and only be read by me?

I’m reminded as I walked into the library today seeing the piles of elm samara, millions upon millions, at the feet of elm trees that have been here for 50 or 60 years, maybe longer. I’m reminded of Robert Frost, who now has a statue beneath those elm trees outside. When asked for advice about how to understand poetry, Frost said: Poetry, or stories, are best read in the light of all the other poems every written, which is not possible. Progress is not the aim, but circulation.

Think in centuries, like the elm.

I think I have to cast way more seeds than I do currently.

That concept of a culture's "canon" is pretty fascinating. Looking at required reading in high school and college, then seeing how society has evolved in spite of or because what is essentially collective exposure to these expressions of art. THEN I think of what my OWN canon is … and why!

Such a gift. Now seeing paper wings everywhere and in many forms. Thank you, Seth. Thank you, elms. Thank you, books and those who love the art of words.