Being thrown in a concentration camp seems to be a common source of anxiety for people in my life. At the tire shop the other day, I ran into my old friend Alex. His eldest son is off to college in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, away from our small city. We all watched this kid grow up to become a star student and a talented actor with a bass singing voice that makes doors rattle. He’s thriving academically. Expectations are reasonably high. He’s also gay. While customers picked out radials, my friend confided that, as a family, they’ve considered emigrating to another country—like New Zealand or Denmark—for a place more tolerant of their son’s sexuality. Recent statements of state politicians have led him to believe that the State of Texas doesn’t recognize his son as human. For them, it’s a short slope to the concentration camp.

Another friend’s parents retired a few years ago in Michigan after raising their family and doing quite well with a construction company. For them, Michigan is being overrun with liberals; the public schools are teaching pornography and jumbling pronouns. They convinced most of their adult children to move their families to Texas, where they built a house with an oversized crawlspace and stored three years of MRE’s. How long before the remnant left in Michigan is corralled into work camps?

Maybe that seems extreme, but unfortunately, there’s enough human history to say “Yeah, we have a tendency to do this sort of thing.” And I have to admit, I don’t want to die in a gulag, either.

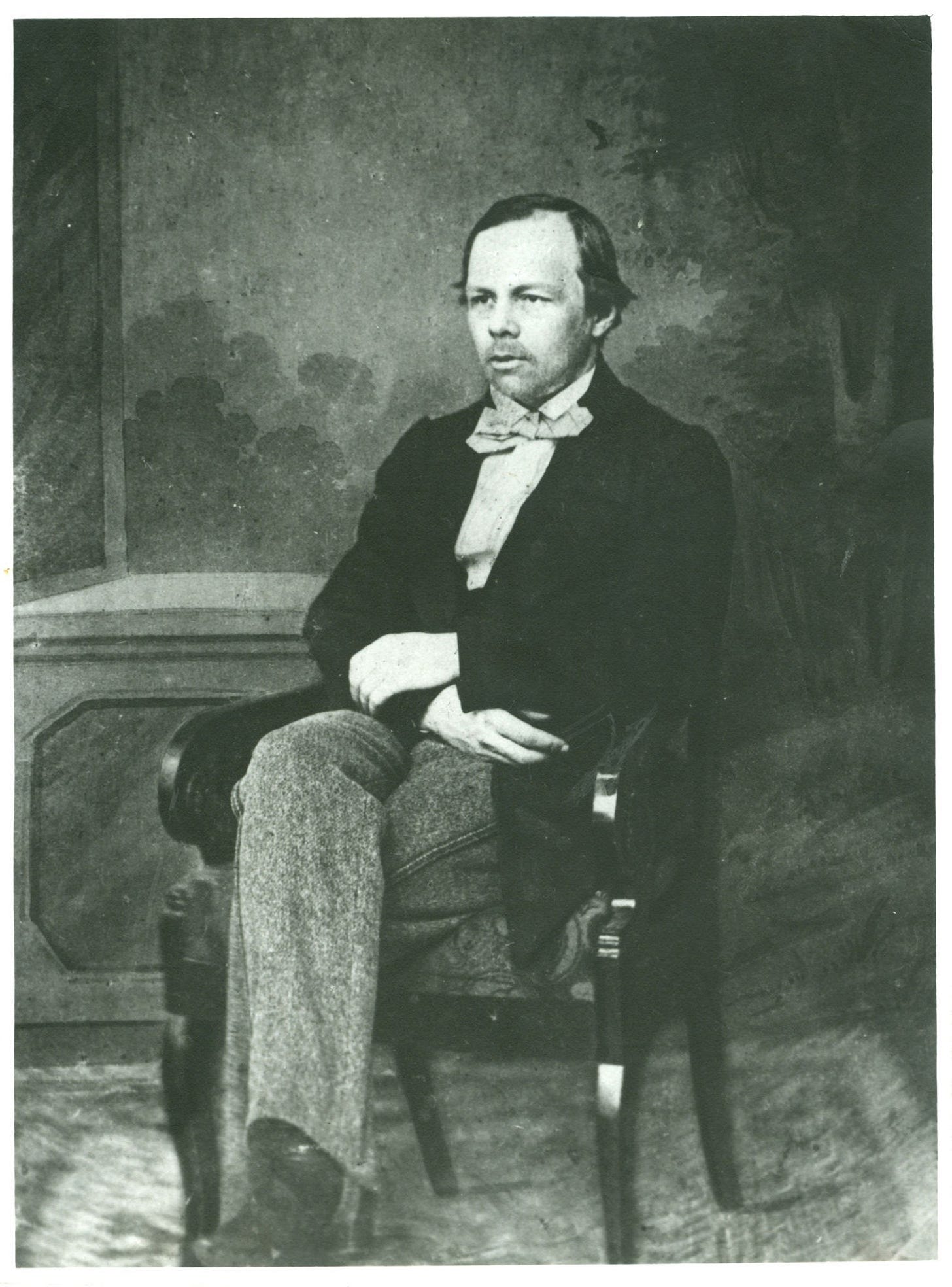

A person can be thrown into a gulag for a lot of reasons. When I was a young writer of twenty, encountering Fyodor Dostoevsky for the first time, I was terrified to learn he’d been sentenced to death for drinking vodka with some questionable characters who influenced his writings to be critical of the government. They were reading a German named Schiller. Young Dostoevsky was spared from the firing squad literally while his blind fold was being knotted, but he still wound up in a Siberian work camp for four years, and served another five years in a penal battalion.

I was twenty in 2001. I could not imagine this happening in America, even as the Patriot Act gave unprecedented access to our private lives. Kanye West could get on a live national broadcast and claim that the president of the United States hated black people and suffer no government backlash. The Dixie Chicks could say they were ashamed of the president—and although they suffered commercially and socially—nary a firing squad was summoned. Perhaps, I thought, gulags were only reserved for fine artists, those purveyors of serious art. So I looked to the vanguard Poetry Magazine to see if any of their poets were being critical of the government. Sure enough, in the twilight of the Bush Administration, Poetry published a poem by Claude Eshleman that I can only categorize as a conspiracy poem, naming specific government officials for orchestrating the September 11th attacks. I worried for Claude, expecting that he would wind up under a waterboard in Guantanamo, but, much to my astonishment, he won government grants from both the National Endowments for the Arts and the Humanities!

As I’ve gotten older and settled into my calling as a poet (or at least calling myself a poet), I have kept Dostoevsky in mind. He returned from his stint in Siberia with even more determination to write. Where did he learn this courage (or foolishness)? His hero, Friedrich Schiller, too had been arrested for writing a play that was critical of corruption in the German government. After his arrest, Schiller was granted French citizenship where he wrote and taught, until their own government corruption resulted in the French Reign of Terror! He retreated from the academy and from writing plays for a few years to quietly work on aesthetic treatises he hoped would revitalize his dramatic plays.

Although Schiller was eventually welcomed back to the theater, his experience of being arrested for writing a play stuck with him and emerged thematically in dramas like Don Carlos and William Tell, both of which portray government overreach into the private lives of citizens.

After his death, Schiller’s works found a massive following in Russia, newly fomenting with revolution. According to the editor of his collected works in Russian, booksellers could almost predict, like clockwork, when a new revolution was forming by how many copies of Schiller they were selling. And what revolutionary idea was Schiller shilling? The freedom of the individual to speak and act under his own compulsion; to be free of the bidding of the king or his downstream dukes and viceroys and provincial clerks stationed in dim outposts. If a person wanted to wake up and plant a crop, or fell a tree, or write a poem—simply make a thing—then he could do so by his own lights without the command or censure of a far flung emperor.

Then in grand St. Petersburg, a young Fyodor Dostoevsky was introduced to the works of Friedrich Schiller. He wrote his brother, “I have [Schiller] by heart, I have spoken his speech and dreamed his dreams.” The brothers Dostoevsky were working on their own translation of the German playwright when Fyodor was arrested.

A person has a lot of time to think in a Siberian gulag. Dostoevsky had been translating Schiller’s Don Carlos and now he mulled it over and over in the freezing camp. In the play, King Philip of Spain fought for absolute control, signing over the lives of a hundred thousand men to die for the sake of his empire. His son Carlos, for whom the play is named, wanted to bring freedom—the autonomy of individuals— to the Spanish people and free his friend, the Marquis Posa so he could return to his quiet life in the province of Malta, no longer under the conscription of the king. The play ends tragically with King Philip sacrificing his own son Carlos to maintain control of his kingdom. In a desperate attempt to quell a rebellion and subdue his son, he calls the old, blind Grand Inquisitor for a solution.

KING

Can you create for me a new religion

that will defend the murder of a son?

GRAND INQUISITOR

Atonement of eternal justice that was

for what God's son died on the cross.

KING

Are you prepared to spread this point of view

throughout all Europe?

GRAND INQUISITOR

Anywhere the Cross is worshiped.

KING

I'm also sinning against nature. Can

you silence that voice as well?

GRAND INQUISITOR

Before the Faith, the voice of nature

has no standing.

KING

I'll place the task of judgment in your hands.

Can I withdraw completely?

GRAND INQUISITOR

Give him to me.

KING

He is my only son. What have I raised him for?

GRAND INQUISITOR

To return to dust rather than to freedom.

To win back the population’s favor, King Philip conspires with the Grand Inquisitor to create a new religion that justifies sinning against nature. The curtain falls as the king hands over his son, but we’re left to imagine what the Inquisitor, instrumentalized by the State, does to Carlos.

Over thin gruel, Dostoevsky mulled the Inquisitor’s power in his icy Siberian cell. What would the Inquisitor’s new religion have looked like had the play continued? by the time he was finally released from his sentence, he had found his own Grand Inquisitor, one whose new religion is more developed than Schiller’s. Dostoevsky’s Inquisitor in Brothers Karamazov says men will give up freedom for food, for materiality—for bread rather than the bread of heaven. This new religion spoken of by Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor tells Christ Himself, as John Simons says, “traditional Christianity has been replaced by a new religion based on materialism.” The Inquisitor, staring Christ in the face, says “The church declared that it would feed the people in Your name, but in the end the people will lay their freedom at our feet and say to us ‘Make us your slaves, but feed us!’”

I think back to my twenty-year-old self, discovering that Dostoevsky and Schiller were imprisoned for merely writing. I was grateful that as far as I could tell, no one was being arrested for being critical of the government’s new power and questionable wars. Claude Eschleman could write a poem full of unfounded conspiracy theories and dark allegations in a major magazine and suffer no consequence. Wasn’t this the dream of Schiller?1

I’d like to believe that poets, citizens, like Eschlemen are able to express themselves freely with no thought of the gulag, but I keep mulling over Schiller’s Inquisitor creating a new religion; mulling again Dostoevsky’s Inquisitor, that the people will say, “Make us your slaves, but feed us!”

What if it’s not the icy gulag that we should be concerned about? Is it the new religion of materialism that actually has imprisoned us? We’re free to say whatever we want, call it the ultimate self-expression, and everyone gets her turn, fed with endowments and publications, likes and retweets. Subject yourself but be fed thinner and thinner gruel. Again, I don’t want to die in a gulag, even if the gulag is a comfortable, suburban home and my gruel is fast food.

Did Dostoevsky escape the Inquisitor? Did Schiller? In his philosophical treatise On the Aesthetic Education of Man, Schiller lays out a series of maxims meant to guide the artist in maintaining independence. “Live with your century,” he says. “But don’t be its creature. Render to your contemporaries what they need, not what they praise.” If those are the guidelines, how can I even participate?

I consider my old friend Alex’s fears for his son. And the ex-Michiganders who share the exact same fears for different reasons. If my art is not helping them put their fears to sleep, then I’m no different than that “kept” Eschlemen lavishing contempt on abstract political figures he knows will never acknowledge him; expressing bile without form as from an abscess; irritating fears into an impotent rage. Schiller says again,

Try your fashioning hand upon their idleness. Drive away lawlessness, frivolity and coarseness from their pleasure, and you will imperceptibly banish them from their actions, and finally from their dispositions. Wherever you find them, surround them with noble, great and ingenious forms, enclose them all round with the symbols of excellence…

And here I must trust the forms laid out by Schiller and Dostoevsky. Their noble, great and ingenious forms did banish my own fears. I don’t want to die in a gulag either, but by their excellence, can I see the schemes of the Inquisitor. And moreso, can I see the heroic Marquis Posa, who was temporarily blinded by the king’s favor, sacrifice himself for his friend and find redemption; and William Tell put himself and his son at hazard to save his neighbor; and Alyosha Karamazov feeding the poor, devoting himself to holiness. And finally have the fortitude to set my fashioning hand upon their idleness.

It’s not the dream of Schiller, but that’s another essay.

One of your best pieces to date, Seth.