This week Amarillo’s famous Cadillac Ranch celebrates 50 years. With 2 million visitors every year, it’s one of the most famous art installations in America.

I’ve modeled the following conversation on Plato’s famous dialogues. If you’ve ever read those dialogues, then you’ll know that they were filled with characters from ancient Athens, and the original readers would have known the people in the conversation. In this case, I’ve decided to include real people from Amarillo who might be involved in official conversations about public art. I’ve imagined a dialogue where Jason Boyett has assembled an informal committee for lunch in a building that Mason Rogers designed—a double restaurant and brewery—which is the first new building in downtown Amarillo in nearly twenty years. Amarillo is nationally famous for two “art installations.” Cadillac Ranch—where ten Cadillacs are buried nose-down along I-40 and are visited by 2 million visitors each year. And the Dynamite Museum—a series of thousands of street signs with odd phrases and images painted on them and installed in residential yards all over Amarillo and recognized as the largest urban art project in the world. Both of these installations were patronized by Stanley Marsh 3, an heir to an oil fortune, whose reputation suffered late in his life.

I know all of the people involved in this dialogue, but I haven’t consulted any of them for this conversation. I don’t mean for this conversation to be completely representative of what they would say, but almost all of their dialogue I “found,” or pulled from public statements the individuals have made. In Jon’s case as a consultant for Marsh’s art estate, I’ve allowed Jon to “speak” on behalf of Stanley Marsh 3 since Mr. Marsh passed away in 2014. The cast descriptions below are pulled from public descriptions of them.

Every city I visit has public “beautification” projects from sculpture installations to murals, and Amarillo is no different. I wanted to think about the implications of public art, or art made with a civic purpose.

The Cast of Interlocutors

Mason Rogers - Architect / Master of Architecture from Catholic University of America

Jon Revett - Associate Professor of Art and Art Program Director at West Texas A&M, and visual artist whose work utilizes patterns of geometric shapes. Jon worked for Stanley Marsh 3 in high school and as a young man, and still serves in some capacity to the Marsh estate as an advisor to Marsh’s “art collection.”

Lytton St. Stephen1 - gender anarchist / non-binary / trans / activist

Jason Boyett - Journalist / Magazine Publisher / Ghostwriter / Podcast Host / Committee Lead / Member of many committees

Jason: Thank you Jon and Lytton for agreeing to have lunch and discuss the future of public art in Amarillo. Mason is running a little late, but we can go ahead without him.

Lytton: I’m honored to be here Jason! As you know, I’m an advocate for restoring the role of the arts and humanities as a means by which to address social justice reform and promote equality and diversity in the upper panhandle.

Jason: Well of course, Lytton. That is why I asked you to join us. As Amarillo looks toward the future, we need to include a diversity of voices. The ideas that we discuss this afternoon will be presented to the official committee and eventually the city council.

Now bear with me as I read from my agenda notes: Amarillo is growing rapidly. With the 2020 census, we have crossed the threshold of two-hundred thousand people. Experts tell us that is a magic number for cities because it means the city has built the appropriate infrastructure to accommodate large growth, raise revenue, and attract a diversity of industry. One consultant hired by the city council predicts that Amarillo will be at six-hundred thousand by 2040. That seems like a distant future, but in terms of city planning, it is a mere blip. That kind of growth in that span of time is migratory—not just families having kids— which means people from all over the United States will be moving here. People who do not know Amarillo’s culture or its history, who don’t vote the same, and who don’t worship the same.

Lytton: Thank gawd.

Jon: Sure, so we’ll need to imagine art from different cultures.

Jason: Exactly Jon. Can we imagine what it will be like to have people moving here from Michigan and Mexico, Colorado and California?

Mason (arriving): Like the grandkids of Tom Joad coming home.

Jason: Ah, Mason! Have a seat.

Mason: Sorry, I’m late. I had trouble finding the place.

Jason: We’re discussing the future growth of Amarillo and the challenges we’ll face with a changing population. I want us to imagine what the next Cadillac Ranch or the next Dynamite Museum will look like.

Jon: Cadillac Ranch is nearly fifty years old and is in bad shape. When Ant Farm buried the Cadillacs in 1974, they were making a statement, but it’s not designed to weather fifty years of our extreme elements.

Jason: They couldn’t have known it would become such a popular attraction. More people visit Cadillac Ranch than the Guggenheim in New York. Let’s discuss why it works as public art, and then think about what Amarillo could do next.

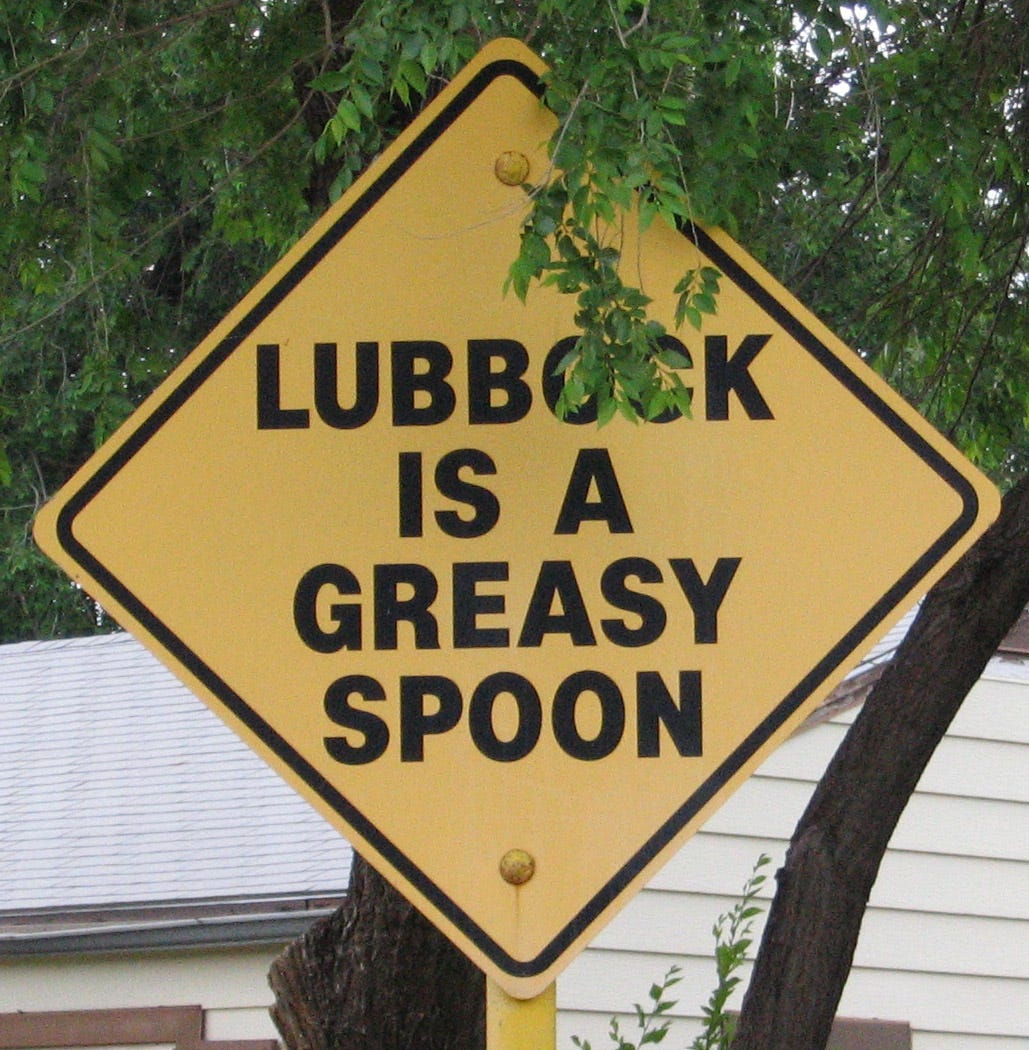

Jon: Your comparison to the Guggenheim might be the place to start. Stanley hated museums. He built a system of unanticipated rewards. And that system was not to go in museums and was not to be seen by the public when they knew they were seeing them. Cadillac Ranch was to come as a surprise. The people who visited Cadillac Ranch came upon it by accident. They were simply driving across the country. Art in a museum programs you to like it or not like it. The Dynamite Museum was so named because it was supposed to blow up, destroy the idea of museums. The fact that you could drive down a residential street, and side-by-side see a stop sign and a sign that says something meaningless like “Dogs barking” will surprise someone.

Mason: If two million people visit every year, does Cadillac Ranch still surprise people?

Lytton: People visit because it’s kitsch. I love kitsch. It’s like seeing the World’s Largest Ball of Twine in Kansas. You buy a can of spray paint, walk out to Cadillac Ranch, paint something like “Lol” or a smiley face or genitalia as performative masculinity, post a selfie with a peace sign and say “I made the pilgrimage and paid my oblations to American decadence.” It’s an ironic way of saying you know what your grandparents couldn’t have known. We paint over what they created and my creation will be painted over in ten minutes.

Jason: So it invites participation from the public.

Jon: I’m not sure the project was conceived as kitsch. The ten Cadillacs that are buried there show the evolution of the tail-fin, which was a technological and style accomplishment for the auto industry from the forties into the sixties. Cadillacs were the most luxurious, maybe most beautiful, cars made in America during those decades. The fact that we buried ten of them—at an angle that matches the pyramids of Giza—along America’s mother road is significant.

Lytton: How can you say most beautiful? That’s a power statement. Grandpa might have thought a Cadillac was beautiful, but I can only see it as our laissez faire dependence on petroleum which led to wars in the Middle East and capitalism’s destruction of the environment. I think the layers of caked spray paint flaking off the Cadillac is beautiful. My beautiful is different than your beautiful, one is not more or less beautiful. The only difference that matters is that we’re at a superior point in history—we can look back on the injustices of the past—and judge how one person’s beautiful led to our present inequalities, and we can avoid that in the future.

Mason: Waiter, can I get two beers? One Budweiser in a can and a Pondaseta I-40 from the tap?

Jason: So we’ll need to be mindful about who we commission to create the art and the social and environmental impact it has. We don’t want to commission another statue of a Confederate general. Especially since Amarillo wasn’t even founded until 1887.

Jon: The art world is obsessed with the identity of the artist.

Lytton: As it should be. The art is secondary. Maybe tertiary. The person who created the art is primary because the identity of the person is prime creation from which all other creations emerge. We attempt to understand our most authentic truths, we attempt to truly hear one’s innermost call from within the depths, while grasping life’s ecstatic temporalities as tightly as possible and being more afraid of the potential for unbeing in the face of compulsory and imposed constructs than being seen for who and what one truly is. The artist who has found one’s Ownvoice is the one whose art we should patronize and deny patronage to artists who subscribe to constructs.

Jason: I’m not sure how to present that to the city council. The council is accountable to the taxpayers for dollars spent on public art. And we’d still need to give direction to that artist concerning materials and budget, possibly subject matter.

Jon: The subject matter seems to me to be the primary focus. You’re right, Jason. We don’t need another Confederate statue in a park. Of course, in 1931, plenty of people in Amarillo thought the statue commemorated a good thing. Opinions change, politics change extremely quickly. By 2040, we could possibly have had four different presidents.

Lytton: And those people in 1931 should be mocked, treated with irreverence. Slavery was patently wrong and they should have known that.

Jon: I’m not saying that. I’m saying that public opinion changes about the subject matter depicted in art. No one remembers who cast the Confederate statue in bronze, but the Confederate subject is problematic. We could avoid problematic representation by using neutral patterns of geometric shapes. A circle has been a circle in all cultures and it adheres to those standards of beauty like symmetry and proportion.

Lytton: Standards of beauty? Are standards of beauty not imposed constructs?

Mason: Waiter, could I get a round of beers for everyone. Same as my order.

Jon: Look, Stanley Marsh wanted to shock people out of their boring, humdrum lives. We wake up every morning and it’s just the same as it was yesterday. And it’s only through art and invention that we reinvent ourselves every morning, that we look in the mirror, that we part our hair anew, that we shine up our teeth, that we smile and say it’s a new world little man, I’m gonna go out and have a great affair today.

When I was younger, I just thought to shock someone was to offend them, be crass, be vulgar. Stanley loved to pick on the prevailing culture, the church goers, the “double pleat people” he’d call them. But Stanley was rich and could afford to fund art projects privately. Now we’re talking about public funds and public approval. No project gets off the ground unless the public approves of it. You have to get the double pleat people to sign on. There are other ways. Do something new, unexpected rather than simply shocking. Figurative art, representational art inevitably diffuses into the political, or gets hacked as propaganda. But the arabesque rarely employs the figural. It’s unexpected, it’s inoffensive because it’s difficult to apply a narrative to it.

Jason: You haven’t said much Mason.

Mason: I’m the least qualified to be here. Jon is a bonafide artist. If you look above you, that twenty foot canvas is his.2 He’s responsible for educating the next generation of fine artists for the region. He has work in galleries all over the country. And apropos to our conversation here, he’s the leading expert and consultant on all things Stanley Marsh.

And Lytton is the smartest person in the room. Did you hear their vocabulary? I’m merely an architect. I put roofs and walls together. There’s not much to it.

Jason: My father was an architect. I know that’s not true. And I invited you.

Mason: Y’all take a drink of the Budweiser our waiter just brought. Bud was the first beer I ever tasted when I was in college. That first sip was so bitter and sour at the same time that I couldn’t even finish the whole beer. But then I drank a lot of Budweiser. I don’t drink it very often now because I’ve found better beers. Craft beers that kind of elevate the materials of beer into something more complete. But I know a lot of people I went to college with only drink Bud, still. That is the height and depth of their taste. I drink one occasionally to remember why I used to drink it, but I’m always reminded of the time I was in Chicago taking the architecture tour, and the guide said that they reversed the flow of the Chicago River so that all of their sewage flows south to St. Louis where they use the water to make Budweiser.

Lytton and Jon, both of you spoke of what we should consider first: the identity of the artist or the subject matter of the artifact? But beauty is the first word of this whole conversation. We can’t sneer at beauty as if we’ve progressed beyond it. Lytton, you speak of beauty like it’s a shackle bolted to concrete. Symmetry and proportion aren’t social constructs that cage you, they’re physics. We don’t want a building that attempts to defy those rules. Especially in our environment. A building built here needs materials that can do their job in temperatures that fluctuate over a hundred and fifty degrees, winds up to seventy miles an hour, to channel water in torrents but also handle the shifting clay that shrinks in a drought, and once every five years carry a snow load. If I didn’t follow those rules, the building would fall down around us, and that is objectively bad. So beauty is tied together with the good. In a world without beauty, which can no longer see it or reckon with it: in such a world the good also loses its attractiveness. Man stands before the good and asks himself why it must be done—why must I build a building that doesn’t fall down when there are so many possibilities of buildings we haven’t explored— the man asks himself why good must be done and not evil? If you’re concerned with justice, then the first word in the conversation is beauty.

If you are concerned with the identity of the artist, then again, beauty is the first word. When you encounter something beautiful—if you haven’t hardened yourself to it and shut yourself off from the language of beauty—then beauty is conceived in you. I think about Homer who wrote The Iliad so beautifully that not only is the poem immortal, but the poem has provided Homer with immortal glory and remembrance. It might even begin to redeem some of those ancestors who Lytton’s namesake would have mocked.

If we are concerned about the future of the city we love and live in, then again beauty is the first word because beauty gives birth to beauty. Jon you got bogged down with the possibility of offensive subject matter, but you’re right. We cannot know what people in 2040 will find offensive. But if we set out to make something beautiful today, then someone else will make something beautiful. Be open to beauty. Converse in the language of beauty. People will either respond with more beauty, and therefore justice because justice implies balance, or they will want to destroy it. Some people cannot perceive beauty any longer. Some will resist it by rejecting it instead of welcoming it with gratitude the joy it offers. Some feel an irresistible urge to deface a beautiful painting. You can bet that our recent murals are going to invite vandalism soon. But we create the beautiful because it is good.

Finally, I’m not sure “public art” will accomplish any of this, in the sense that the city council approves and commissions these works. I’m not an artist. I’m an architect. I hope my buildings are beautiful in form, but they have a purpose besides beauty. This is a restaurant. I’m designing a dentist’s office right now. Public art has a purpose that is not simply to be beautiful. It’s like a museum that programs you what to think. We need artists in the margins creating surprises, creating cultural estuaries, generously giving their gifts to the community. Let’s not make it difficult for them.

Now let’s drink this Pondaseta I-40. It’s objectively better than Budweiser. Cheers to Amarillo!

Works Cited

Kathy Reed. “Plutonium Circus Pentax Lab Amarillo TX.” YouTube, 8 Dec. 2022,

Plutonium Circus Pentax Lab Amarillo TX

Meljac, Eric. Email to Seth Wieck. “Zoom Poetry Reading by Lytton St. Stephen.” 18 August 2020.

Reeve, C.D.C. Plato on Love. “Symposium.” Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. Indianapolis, 2006.

“Amarillo Ramp.” Holt-Smithson Foundation. https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/amarillo-ramp. Accessed 7 Dec. 2022.

Lytton St. Stephen legally changed their name when they began transitioning. They admired the British author Lytton Strachey’s role in the Bloomsbury group. Lytton Strachey famously lampooned earlier generations of British literature while at the same time being their literary heir.

The restaurant Crush owns and displays a Jon Revett original painting that is a series of circles that was inspired by a dining experience in Spain.